Types

In C++ most types have the same or a similar name as in C#, but not always. This is a table that hold a comparison of all fundamental types you should know about:

| Type: | C# | C++ (classic) | C++ (modern) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32 bit floating | float | float | - |

| 64 bit floating | double | double | - |

| 128 bit floating | decimal | - | - |

| 8 bit integer signed | sbyte | char | int8_t |

| 8 bit integer unsigned | byte | unsigned char | uint8_t |

| 16 bit integer signed | short | short | int16_t |

| 16 bit integer unsigned | ushort | unsigned short | uint16_t |

| 32 bit integer signed | int | int | int32_t |

| 32 bit integer unsigned | uint | unsigned int | uint32_t |

| 64 bit integer signed | long | long long | int64_t |

| 64 bit integer unsigned | ulong | unsigned long long | uint64_t |

| boolean | bool | bool | - |

| character | char | char | char16_t |

| string | string | string | - |

| null | null | nullptr | - |

References

In C++ classes are value types by default, not reference types like in C#.

Passing a class instance by reference to a function in C# is:

// csharp

void Example(Class instance)

{

// changes the original instance

instance.variable = 1;

// this creates a copy

Class instance_copy = instance.Clone();

}

Passing a class instance by reference to a function in C++ is:

// cpp

void Example(Class& instance)

{

// changes the original instance

instance.variable = 1;

// this creates a copy

Class instance_copy = instance;

}

You can also pass a class instance in C++ with a pointer:

// cpp

void Example(Class* instance_ptr)

{

// changes the original instance

instance_ptr->variable = 1;

// changes the original instance

(*instance_ptr).variable = 1;

// this creates a copy

Class instance_copy = *instance_ptr;

}

Memory

Stack:

When creating a variable in C++ it uses the stack by default. Memory on the stack is local to its scope and gets released automatically when the variable goes out of scope.

Heap:

When you want memory to exist outside of the scope it is created in, you must allocate memory for it on the heap.

You can allocate memory on the heap using malloc() and release it using free().

But a better alternative is using auto variable = new Type(); and release it using delete variable;

Leaks:

In C++ heap memory does not automatically free when the application terminates. and in both C++ and C# OpenGL data like buffers and textures in vram also dont automatically free when the application terminates. Generally speaking the os will reclaim unfreed memory when the application terminates, but relying on this is bad practice.

Pointers

Basic:

Raw pointers in C++ work the same as in C#, the syntax is the exact same:

int x = 1;

int* ptr = &x;

int y = *ptr;

it doesnt matter where in a pointer you use a space as it will all work:

int* ptr = &x;

int *ptr = &x;

int*ptr = &x;

Smart:

In modern idiomatic C++ there is a safer approach to pointers, called smart pointers.

There are 3 types of smart pointers: std::unique_ptr std::shared_ptr std::weak_ptr,

to use them include the #include <memory> header in your code.

Fundamentally what a smart pointer is, is a pointer that automatically frees the memory of whatever it points to when the pointer itself goes out of scope.

Unique Pointer:

This pointer has ownership over whatever it points to, if it goes out of scope and gets dropped of the stack, so does the memory it points to.

What makes this one different from the other smart pointers:

- there can only be one unique pointer per object

- the object lifetime is tied to the unique pointer, unless ownership is moved

// cpp

#include <memory>

void test()

{

// making a unique pointer

std::unique_ptr<Foo> foo_ptr = std::make_unique<Foo>();

// No need to delete, gets freed at end of scope

}

Shared Pointer:

What makes this one different from the other smart pointers:

- there can be many shared pointers per object

- target object lives as long at least one shared pointer exists

// cpp

#include <memory>

void test()

{

// making a shared pointer

std::shared_ptr<Foo> sp_1 = std::make_shared<Foo>();

// sharing ownership

std::shared_ptr<Foo> sp_2 = sp_1;

// get amount of shares

int shares = sp_1.use_count(); // there are now 2 shares

// you can manually drop a share like so

sp_2.reset();

int shares = sp_1.use_count(); // there is now 1 share

// at the end of this scope the first pointer also drops

// now since there are no more shares the object is freed

}

Weak Pointer:

What makes this one different from the other smart pointers:

- weak pointers dont have any ownership

- weak pointers can only be used with shared pointers, not unique pointers

- there can be many weak pointers per object

- weak pointers dont increase the amount of shares like a shared pointer

- weak pointers dont own an object so the object’s lifetime is not tied to the weak ptr

- all weak pointers expire when the last shared ptr gets dropped

- weak pointers dont point to anything directly, so you cant simply deref them

- to use a weak pointer you must convert it to a temporary shared pointer

// cpp

#include <memory>

void test()

{

// making a shared pointer

std::shared_ptr<Foo> sp = std::make_shared<Foo>();

// sharing ownership but with weak pointer

std::weak_ptr<Foo> wp = sp;

// get amount of shares

int shares = sp.use_count(); // still 1, weak ptr didnt add a share

// directly dereferencing a weak pointer wont work

// *wp and wp-> cause a compile time error

// to use a weak pointer you must convert it to a temp shared pointer

// lock creates a shared pointer if the object still exists otherwise a nullptr

auto temp_sp = wp.lock();

if (temp_sp != nullptr)

{

// safe to use *temp_sp or temp_sp->

// while the temporary shared pointer exists there is an extra share

int shares = sp.use_count(); // now 2 temporarily

// drop temp shared pointer

temp_sp.reset();

}

// destroy the only and last shared pointer with ownership

sp.reset();

// now since there are no more shares the object is freed

// the weak pointer like the object doesnt exist anymore

bool does_object_exist = wp.expired();

// the weak pointer still exists but cant be locked anymore

}

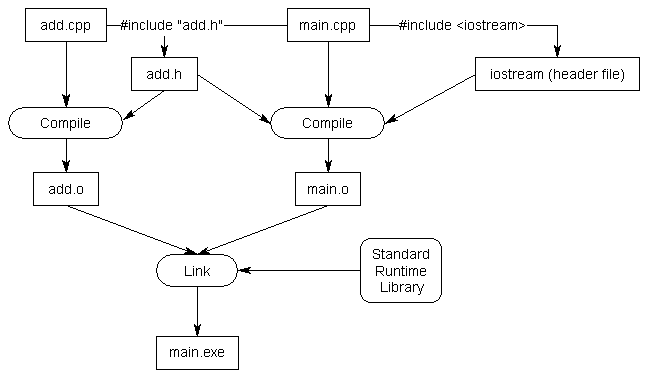

Headers

What are they?:

In C# you can acces functions that are in a different .cs file by just making them both use the same namespace. In C++, its a little bit more complex.

Header files can be seen as an outline of all the functions contained in a .cpp file.

All code goes in .cpp files, and then every file has a header .hpp file with the same exact name which contains all the declarations (names) of your functions.

Using headers help the compiler understand how source files are connected, which is one of the reasons C++ code compiles so very fast compared to C# code.

How are they used?:

You can access code from other files only by using #include "file.h" at the top of your code. Which will simply copy the entire header to that point.

You can include a header in 2 ways: #include "file.h" or #include <file.h>. Using quotes will search the header in your current directory and using angled brackets will search the header in the include directory.

Further Reading:

Standard Library

There are a set of build in header libraries you can use for common operations called the Standard Libary or std for short. You can look at the standard library as the conceptual equivelant to the System namespace in the C# language, it provides libraries for common operations like input and output and file operations as well as containers like strings, lists, dictionaries and others.

The most commonly used headers in the standard library:

C++ Standard Library:

| Header | Description | Contains |

|---|---|---|

<iostream> | Console input/output | std::cin / std::cout |

<fstream> | File input/output | std::fstream / std::ifstream / std::ofstream |

<string> | String container | std::string / std::to_string |

<vector> | Dynamic array container | std::vector |

<memory> | Smart pointers | std::unique_ptr / std::shared_ptr |

<utility> | Utility components | std::move / std::swap / std::pair |

Plain C Standard Library:

| Header | Description | Contains |

|---|---|---|

<stdlib.h> | General system utilities | malloc / free / exit |

<stdio.h> | General input/output | printf / scanf / fopen / fclose |

<stdint.h> | Fixed width integer types | int64_t / uint64_t |

<string.h> | String and memory utils | strcpy / strlen / memcpy |

<stdbool.h> | Access to the bool type | bool / true / false |

<stddef.h> | Several common definitions | size_t / offsetof |

<math.h> | Math utility functions | sin / cos / sqrt / pow |

If you are like me and you write C++ is a very plain C kind of way and want access to malloc and free

and other stuff from the plain C standard library. You could just include <stdlib.h> and it will work,

but since plain c doesnt have namespaces, all the standard library features will pollute the global namespace.

This can be prevented by using the C++ wrappers for the plain C std libraries. It works like this, take the name

of the header you want: <name.h> and add a c in from of the name and remove the .h at the end,

this way <name.h> becomes <cname>, and just like that all the stuff from the library is accesable

under the std:: namespace, just like all C++ standard libraries. Now you can

use malloc like std::malloc and free like std::free, this is

the recommended way to use the standard library for plain C in modern C++ code.

Initialization

Stack / Heap:

C++ allows you to initialize objects on the stack or the heap. But In C# you mostly don’t get to choose, classes will be on the heap most of the time like most other reference types,

and structs on the stack most of the time like most other value types, but structs are in some cases not on the stack but on the heap too, this is something C# decides at runtime based on a number of factors like for example its scope.

So generally speaking in C# you have not much control over what gets allocated on the stack and what on the heap. But generally you can assume reference types are on the heap, and value types are on the stack.

And in C# you must always use the new keyword when creating an object it doesnt matter if the object you are creating is a reference or value type or if its on the stack or on the heap, new always gets used,

while in C++ new means initialization on the heap. So if you want to initialize something on the heap in C++, just pick any of the normal ways you would initialize/create a variable on the stack, and use the new keyword

after the equal sign and make the returning type a pointer, so for example take this stack initialization: Type test = Type(x); and turn it into Type* test = new Type(x); to make it a heap initialization.

Uniform Initialization:

One thing to note is that in C++11 the syntax for initializing was overhauled to make it more consistent and flexible.

This new syntax uses {} curly braces. The new syntax goes by different names but they generally all mean the same thing.

You will often hear it being called Uniform Initialization or List Initialization or Brace Initialization, but they all refer to the same thing.

C++ Initialization Syntax History:

// below all the ways to initialize organized by version it was added:

// C89

Type test; // uninitialized

Type test = {0}; // default value

Type test = {x, y, z}; // for structs and arrays

// C99

Type test = { .foo = x, .bar = y }; // for structs and arrays

// C23

Type test = {}; // default value (already in C++11)

// C++98/03 (inherited everything from C89)

Type test(x); // uses constructor

Type test = Type(x); // uses constructor

// C++11

Type test{x}; // uses constructor

Type test = Type{x}; // uses constructor

Type test{}; // default value

Type test = Type{}; // default value

Type test = {}; // default value

Type test = Type{x, y, z}; // for structs and arrays

Type test{x, y, z}; // for structs and arrays

// C++20

Type test{ .foo = x, .bar = y}; // for structs and arrays

Type test = { .foo = x, .bar = y}; // for structs and arrays (already in C99)

C# initialization:

Type test; // uninitialized

Type test = default; // default value

Type test = new Type(); // uses default constructor

Type test = new Type() { foo = x, bar = y }; // explicit member init

Type test = new Type() { x, y, z }; // works on collections

Type test = {x, y, z}; // works on arrays

Type test = [x, y, z]; // works on collections

Copy Initialization / Copy Assignment:

Copy initialization is very different from copy assignment, even though the syntax for both is nearly identical.

The syntax for initialization is Type x = value; and for copy assignment is x = value, the syntax is similar but the semantics are different.

What copy initialization does is call a constructor with the value to the right as its argument, while copy assignment takes a pre-existing object and modifies it,

by copying a different value to itself, often using an overloaded copy operator. In short a copy assignment doesnt call a constructor but the copy operator instead.

| Term: | Syntax: | Calls: |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Initialization | Type x(value); | constructor |

| Direct Brace Initialization | Type x{value}; | constructor or initializer list |

| Copy Brace Initialization | Type x = {value}; | constructor or initializer list |

| Copy Initialization | Type x = value; | copy constructor |

| Move Initialization | Type x = std::move(value); | move constructor |

| Copy Assignment | x = value; | copy operator (not initialization) |

| Move Assignment | x = std::move(value); | move operator (not initialization) |

The constructors and operators used here can be fully custom implemented for your custom type by simply implementing these function signatures in your type:

T(T); // constructor

T(T&); // copy constructor

T(T&&); // move constructor

T& operator=(T&); // copy assignment operator

T& operator=(T&&); // move assignment operator

Here is a simple example of how those signatures might be implemented:

class Foo

{

public:

// constructor

Foo( /* arguments */ )

{

// implement logic

}

// copy constructor

Foo(const Foo& other)

{

// implement logic

}

// move constructor

Foo(Foo&& other)

{

// implement logic

}

// copy assignment operator

Foo& operator=(const Foo& other)

{

// implement logic

return *this;

}

// move assignment operator

Foo& operator=(Foo&& other)

{

// implement logic

return *this;

}

}

Things to remember about initialization:

- C++ gives more control over stack vs heap

- C++ the new keyword is for heap allocation

- C++ gives more control about when a copy is performed

- C++ generally speaking the modern curly brace syntax is the best

- C++ copy initialization is very different from copy assignment

- C# always requires the new keyword for any object creation

- C# most of the time reference types are on the heap but not always

- C# most of the time value types are on the stack but not always

Public / Private

In C# you can put public or private before any member of a class like so:

// csharp

class Person

{

public float a;

private float b;

public float c;

}

In C++ you put all public member under public: and all private members under private: like so:

// cpp

class Person

{

public:

float a;

float c;

private:

float b;

}

Structs

In C/C++ you define structs syntactically slightly different than in C#

In C# you define a scruct like this:

struct Point

{

int x;

int y;

}

In C++ you define a struct like this:

struct Point

{

int x;

int y;

}; // <- semicolon is required

In plain C you define a struct like this:

typedef struct Point // <- typedef is required

{

int x;

int y;

} Point; // <- typedef is required

If you plan on writing plain C instead of C++ then there are a couple more ways to declare a struct.

The rules for which do not apply when writing C++, for that usecase only struct Point { ... }; is really commonly used,

since in C++ it automatically creates a type without requiring typedef to be used.

In plain C you can write a struct declaration in one of the following ways:

| Form | Has Tag | Has Typedef | Info |

|---|---|---|---|

typedef struct Point { ... } Point | Yes | Yes | Modern way |

struct Point { ... }; | Yes | No | Classic way |

typedef struct { ... } Point; | No | Yes | Uncommon |

struct { ... } Point; | No | No | Uncommon |

Examples showing each form of declaring a struct in plain C syntax:

// modern way

typedef struct Point {

int x;

int y;

} Point;

// classic way (no typedef)

struct Point {

int x;

int y;

};

// uncommon (no tag)

typedef struct {

int x;

int y;

} Point;

// uncommon (no tag or typedef)

struct {

int x;

int y;

} Point;

Lambda Expressions

A lambda expression like in C# is a lambda calculus function. In simple terms it can be described as an inline function.

The basic structure of a lambda:

- csharp:

(input)=>{body}; - cpp:

[catch](input){body};

This is how lambdas in C# look:

// csharp

// single line lambda

var add = (int a, int b) => a + b;

// multi line lambda

var add_and_mult = (int a, int b) =>

{

var x = a + b;

var y = x * 2;

return y;

};

This is how lambdas in C++ look:

// cpp

// single line lambda

auto add = [](int a, int b) { return a + b; };

// multi line lambda

auto add_and_mult = [](int a, int b)

{

auto x = a + b;

auto y = x * 2;

return y;

};

// lambda with explicit return type

auto add = [](int a, int b) -> int

{

return a + b;

};

When using C++ lambda expressions also have the ability to capture variables from their surrounding scope.

Capturing determines how variables from the surrounding scope are made available to inside the lambda.

You determine how do capture variabled based on what you place inside the [ ] capture brackets.

// cpp

int first = 10;

int second = 20;

// capture all surrounding variabled by value

auto lambda = [=](int a)

{

a = first + second;

first = a; // doesnt change the original

};

// capture all surrounding variabled by reference

auto lambda = [&](int a)

{

a = first + second;

first = a; // changes the original

};

// captures 'int first' by value and 'int second' by reference

auto lambda = [first, &second](int a)

{

a = first + second;

first = a; // doesnt change the original

};

// captures 'int first' by reference and 'int second' by value

auto lambda = [&first, second](int a)

{

a = first + second;

first = a; // changes the original

};

Trailing Return Types

In C++ you can use something called trailing return types, which is just a different syntax for declaring an explicit return type of a function or a lambda.

Instead of placing the return type before the function name, it is placed after the parameter list using the -> syntax.

The syntax for declaring an explicit return type is auto foo() -> type { } instead of the more usual type foo() { } which you are used to as a C# developer.

These are all the ways you can declare an explicit return type in C++ syntax:

// cpp

// normal

int Add(int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}

// trailing

auto Add(int a, int b) -> int // notice the "-> int"

{

return a + b;

}

// trailing (lambda)

auto add = [](int a, int b) -> int // notice the "-> int"

{

return a + b;

};

Operator Overloading

In C# operator overloading works like this:

// csharp

public static Type operator +(Type a, Type b)

{

return new Type(a.value + b.value);

}

In C# you always need to make an operator overload public and static, in C++ you dont.

Also as you can see for C# we use the new keyword because that makes the object exist on the heap and it returns a type by reference, thats default for C#.

In C++ operator overloading works like this:

// cpp

Type operator +(Type& b)

{

return Type(this->value + b.value);

}

Also as you can see for C++ we dont use the new keyword because in C++ everything is a value type by default which are on the stack, the new keyword makes objects on the heap.

Arrays / Lists

Important differences:

- In C# you write

int[] name, while in C++ you writeint name[], it differs where you place the brackets. - In C# arrays are generally on the heap and made with

new, in C++ arrays can be both on the stack or heap - In C#

int[][]is a jagged array while in C++int[][]is a multidimensional array. - In C++ an array can not be copied by value

int foo[] = bar;, must usememcpyinstead. - In C++ an array can not be returned from a function by value, only by pointer.

- In C++ a list is called a vector (yes thats really confusing).

In C# you use arrays like so:

// csharp

// simple array

int[] array = new int[8]; // create

int value = array[0]; // index

// multidimensional array

int[,] array = new int[8, 8]; // create

int value = array[0, 0]; // index

// jagged array (array of arrays)

int[][] array = new int[8][]; // create

int value = array[0][0]; // index

In C++ you use arrays like so:

// cpp

// simple array

int array[8]; // create

int value = array[0] // index

// multidimensional array

int array[8][8]; // create

int value = array[0][0]; // index

In C# you use lists like so:

// csharp

// create list

List<int> list = new List<int>();

// get length of list

int length = list.Count;

// add to list

list.Add(4);

// remove third element from list:

list.RemoveAt(2);

// index list

int value = list[0];

// clear list

list.Clear();

In C++ you use lists (called vectors in c++) like so:

// cpp

// create vector

vector<int> vector;

// get length of vector

int length = vector.size();

// add to vector

vector.push_back(4);

// remove third element from vector

vector.erase(vector.begin() + 2);

// index vector

int value = vector[0];

// clear vector

vector.clear();

Array Pointer Decay

Arrays decay, that means that they implicitly convert to a pointer when used as a value in most expressions or assignments,

so that array type int[] is implicitly converted to a pointer type int*, pointing to the first element of the array.

This makes arrays non assignable (can’t be copied by value), and for this reason arrays are basically the only type in plain c

that can not be considered to be a value type. The reason the language works like this is to prevent big arrays that take a lot

of memory from getting copied around for no reason. Arrays can still be copied if needed by using memcpy if needed.

// plain c

int array[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

// both of these lines work the same

int* ptr = array; // array decays to &array[0]

int* ptr = &array[0];

Passing to or from functions:

Because arrays can not be assigned due to decay, they can not be passed or returned from a function by value, only by pointer, because passing a variable as a function argument is basically just a copy assignment that copies the value to the argument.

// plain c

// you cant pass an array to a function by value

void foo(int array[]) { ... }

// you can however pass an array to a function by pointer

void foo(int* array_ptr) { ... }

// you cant return an array from a function by value

int[] foo()

{

int array[5];

return array; // ERROR: cant return array

}

// you can however return an array from a function by pointer

int* foo()

{

// allocate array on the heap

int* array = malloc(5 * sizeof(int));

// return pointer to array

return array;

}

Pointer Aritmatic:

Because arrays decay to pointers, c and cpp allows you to use an array pointer as if it was an array, you can index or increment an array pointer like its an array itself, this is called pointer aritmatic.

// plain c

// examples of array pointer aritmatic

int array[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

int* ptr = arr; // array decays to pointer

// access elements via pointer arithmetic

int first = ptr[0]; // ptr[0] == *(ptr + 0)

int second = ptr[1]; // ptr[1] == *(ptr + 1)

// incrementing the pointer

ptr++; // ptr now points to the second element

int second = ptr[0];

How to copy by value anyway?

// plain c

#include <string.h> // <- memcpy comes from here

// declare arrays

int array[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

int copy[5];

// copy data by value to make a true copy

memcpy(copy, array, sizeof(array));

True value type arrays in C++:

Because C++ inherited the design of C, it added a true value type array for those who need it.

The type is std::array<> and comes from the <array> header. This type is a true value type,

it will not decay to a pointer, it can be passed by value, passed or returned from a function,

and can be copied because it is assignable.

// cpp

#include <array>

std::array<int, 3> first = {1, 2, 3};

std::array<int, 3> second;

second = first; // full copy is performed

Conclusion:

- Arrays are non-assignable (can’t be copied by value).

- Arrays are basically the only type in c that is not a value type.

- Arrays cannot be returned from or passed to functions by value, only by pointer.

- The language works this way to avoid copying large amounts of memory unnecessarily.

- If you need to copy an array you can use

memcpyfrom the<string.h>header. - You can index an array by pointer using pointer aritmatic.

- In C++ there is

std::array<>which will not decay.

Generics / Templates

In C# you create generics like so:

// csharp

// generic function

void Print<T>(T value)

{

Console.WriteLine("value: " + value);

}

// generic function with multiple parameters

void Print<T1, T2>(T1 a, T2 b)

{

Console.WriteLine("a: " + a + " b: " + b);

}

// generic class

class Box<T>

{

T value;

}

In C++ you create generics like so:

// cpp

// generic function

template <typename T>

void Print(T value)

{

cout << "value: " << value;

}

// generic function with multiple parameters

template <typename T1, typename T2>

void Print(T1 a, T2 b)

{

cout << "a: " << a << " b: " << b;

}

// generic class

template <typename T>

class Box

{

T value;

};

Strings

In C# you use strings like so:

// csharp

// creating a string

string hello = "hello";

// combining strings

string combined = hello + "world";

// comparing strings

bool test = ("apple" == "orange");

// number to string

int age = 22;

string message = age.ToString() + " years old";

// get length of string

string test = "test";

int length = test.Length;

// indexing a string

string test = "test";

char index = test[0];

In C++ you use strings like so:

// cpp

// creating a string

std::string hello = "hello"; // c++ style

char hello[] = "hello"; // plain c style

char* hello = "hello"; // plain c style

// combining strings

std::string combined = hello + "world";

// comparing strings (you cant directly compare raw strings bc they are just pointers)

bool test = std::string("apple") == std::string("orange"); // c++ style

bool test = strcmp("apple", "orange") == 0; // plain c style

// number to string

int age = 22;

std::string message = std::to_string(age) + " years old";

// get length of string

std::string test = "test";

int length = test.length();

// indexing a string

std::string test = "test";

char index = test[0];

Immutables And Statics

In both languages there is commonly some confusion about the differences between immutable variables,

Because the keywords const and static have a different meaning in both languages.

And both languages add extra keywords readonly (C#) and constexpr (C++), which adds to the confusion.

In C# you use immutables and statics like so:

// csharp

// compile time immutable (also static by default)

const int test = 1;

// runtime immutable

readonly int test = 1;

// shared mutable (shared across all instances)

static int test = 1;

In C++ you use immutables and statics like so:

// cpp

// compile time immutable

constexpr int test = 1;

// runtime immutable

const int test = 1;

// shared mutable (shared across file scope)

static int test = 1;

Conclusion:

- C#

const≈ C++constexpr(compile-time immutable) - C#

readonly≈ C++const(runtime immutable) - C#

static≈ C++static(shared across a scope)

Header Guards

Imagine you have 4 different C++ files that all use library.h and so all 4 different files do #include "library.h", now what happens is that when compiling the code

the library gets included 4 times, and because of this it will give an error, because the declared functions in the header file are basically introduced 4 times into your code.

To make sure that no duplicate function declarations get introduced due to multiple files including a header file we use something called header guards.

A header guard makes sure that a header only gets included once in the compilation with the help of the preprocessor even if multiple files need to include the header.

Consider you have first.cpp like this:

// cpp

#include "library.h"

void func()

{

library::SomeFunction();

}

And you have second.cpp like this:

// cpp

#include "library.h"

void func()

{

library::SomeFunction();

}

Now if we compile this with g++ first.cpp second.cpp -o program.exe, the code inside library.h will exist double because we included the header twice in our code.

We can fix this by putting a header guard inside the library.h file like so:

// cpp

#ifndef LIBRARY_NAME

#define LIBRARY_NAME

// the library header code in here

#endif

Now if we compile the code, when the preprocessor processes the code,

it will see if the header is already included somewhere once and will ignore further inclusions,

Allowing us to use the header from multiple C++ files without duplicate declaration errors.

Because #ifndef checks if LIBRARY_NAME was defined somewhere already indicating the file was already included,

and if not then it uses #define to make sure next time it is defined.

Making it so the contents of the header only get included once during the compilation.

Optional Header Only Libraries

To avoid having to work with the terrible build system ecosystem of C++, developers often put an entire library in only a header file. But some of these libraries actually also have a way to dynamically link against the lib. So what they do is put both a header interface only part in the header for dynamic linking, and optionally a full library implementation in the header hidden behind a conditional compilation define.

Such libraries will often ask you to put a define before the header include:

// cpp

#define LIBRARY_NAME_IMPLEMENTATION

#include "library_name.h"

The reason for this is that the content of the header is structured like so:

// cpp

// forward declarations only (for dynamic linking)

int some_function(int);

// optional implementation (for using header only)

#ifdef LIBRARY_NAME_IMPLEMENTATION

int some_function(int) { /* implementation */ }

#endif

So that if LIBRARY_NAME_IMPLEMENTATION is defined,

you are telling the preprocessor to use the library implementation

embedded in the header instead of linking against a dynamic library holding the implementation.

But there is an issue with this way of doing things. If you have several source files in which you want to include this header and you define LIBRARY_NAME_IMPLEMENTATION above

each of them, you would get an error because you are not allowed to define the same symbol multiple times. There is a solution to this, which is having a seperate libs_impl.cpp file where every header library gets defined once like this:

// cpp

// libs_impl.cpp

// first library

#define LIBRARY_A_IMPLEMENTATION

#include "library_a.h"

// second library

#define LIBRARY_B_IMPLEMENTATION

#include "library_b.h"

// third library

#define LIBRARY_C_IMPLEMENTATION

#include "library_c.h"

Then in all the other source files in which you want access to the library you only add #include "library_name.h" to the top, and no implementation define above it.

That way many files can use the library because there will be only a single implementation define for the library in the entire codebase.

Preprocessor

The preproccesor runs right before compiling the code to assembly, and basically is a form of compile time programming.

It resolves things like macros and include directives, aswell as conditional compilation.

You can look at the preprocessor as tiny scripting language for parsing C++ files. This ’language’ has only 12 very simple keywords, called preprocessor directives,

which are basically commands you give the preprocessor that modify your code during compile time.

Both C/C++ and C# have 12 preprocessor directives, but each language has 3 ones that are unique to that language, and of the 9 preprocessor directives that both C/C++ and C# have in common only 6 work exactly the same.

Here is a table showing which directives the languages have in common:

| # | Directives | C / C++ | C# | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | #define | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Defines a macro or symbol |

| 2 | #undef | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Undefines a macro or symbol |

| 3 | #if | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Compile time if statement |

| 4 | #elif | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Compile time if else statement |

| 5 | #else | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Compile time else statement |

| 6 | #endif | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Ends a compile time conditional |

| 7 | #line | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Changes the reported line number |

| 8 | #error | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Generate a compilation error |

| 9 | #pragma | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | Provides an instruction to the compiler |

| 10 | #include | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | Copies the contents of a file to that line |

| 11 | #ifdef | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | Checks if a symbol is defined |

| 12 | #ifndef | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | Checks if a symbol is not defined |

| 13 | #warning | ❌ No | ✅ Yes | Generates a compiler warning message |

| 14 | #region | ❌ No | ✅ Yes | Marks the start of a collapsable region |

| 15 | #endregion | ❌ No | ✅ Yes | Marks the end of a collapsable region |

Out of the 9 preprocessor directives that C/C++ and C# have in common, there are 4 of them that do something different depending on the language:

| # | Directives | C / C++ Behaviour | C# Behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | #define | Defines a macro or symbol | Defines a symbol |

| 2 | #undef | Undefines a macro or symbol | Undefines a symbol |

| 3 | #if | Evaluates an expression | Checks if a symbol exists |

| 4 | #elif | Evaluates an expression | Checks if a symbol exists |

In C/C++ #define creates a macro. What is a macro? A macro is basically a text substitution.

// cpp

#define PI 3.14 // the word PI gets replaced by 3.14

int main()

{

std::cout << PI << std::endl; // prints 3.14

}

In C# #define creates a only a symbol and not a macro. It doesnt substitute text.

// csharp

#define DEBUG // only defines a symbol

static void Main()

{

#if DEBUG

Console.WriteLine("Running in debug mode"); // runs if DEBUG is defined

#endif

}

In C/C++ you can even write function like behaviour using macros:

// cpp

#define SQRT(x) ((x) * (x))

int main()

{

// "SQRT(x)" is replaced by "((x) * (x))"

std::cout << SQRT(5) << std::endl;

}

Function Pointers

In C# if you want a reference to a function to for example pass as to another function as parameter you will probably have used an delegate or its Action abstraction.

In C and C++ you reference functions by having a direct pointer, pointing to the function. The function can then be called using that pointer.

There is a specific syntax for function pointers, this output_type (*ptr_name)(input_params); being the basis of declaring a function pointer.

Simple example of a function pointer:

// declare a function pointer, pointing to Foo

void (*foo_ptr)(void) = &Foo;

// dereference and call the function pointer

(*foo_ptr)();

// call with implicit dereference (works too)

foo_ptr();

Here is another example of declaring some function pointers:

// creating a pointer that points to a func returning nothing

void (*foo_ptr)() = &Foo;

// creating a pointer that points to nothing yet

void (*bar_ptr)() = NULL;

// creating a pointer that points to a func that takes and returns nothing

void (*baz_ptr)(void) = &Baz;

// creating a pointer that points to a rounding function

int (*round_ptr)(float) = &Round;

// creating a pointer that points to a function that adds floats

float (*add_ptr)(float, float) = &Add;

Using typedef on function pointers:

// this declares a single pointer variable named Foo

void (*Foo)(void);

// this creates a type alias called Foo

typedef void (*Foo)(void);

// same as: "void (*func_ptr)(void)";

Foo func_ptr;

// you can use the alias to pass the ptr

SomeFunction(Foo func_ptr);

Casting a function pointer:

// creating the FuncPtr type

typedef void (*FuncPtr)(void);

// getting a function pointer to a dll

void* fn = dlsym(...);

// casting FuncPtr before calling

((FuncPtr)fn)();

// creating the AddFuncPtr type

typedef float (*AddFuncPtr)(float, float);

// getting a function pointer to a dll

void* fn = dlsym(...);

// casting AddFuncPtr before calling

float added = ((AddFuncPtr)fn)(1.0f, 2.0f);

Other noteworthy stuff:

// these two ways work the same (the '&' is optional)

void (*foo_ptr)() = &Foo;

void (*foo_ptr)() = Foo;

// these are different

void (*foo_ptr)(); // function taking an any number of parameters

void (*foo_ptr)(void); // function taking no parameters

// these two ways work the same (parameter names are optional)

float (*foo_ptr)(float a, float b);

float (*foo_ptr)(float, float);

Member Definition Outside The Class

Sometimes in C++ you will see something like this:

void ClassName::MethodName()

{

// some code

}

Why is the :: syntax used? And why is ClassName there? It is the syntax for defining (implementing) a class’s method outside of the class itself,

often even in another file entirely, with the class often only being declared in a header file:

Inside the ClassName.h file:

// cpp

class ClassName

{

public:

void MethodName(); // declaration

};

Inside the ClassName.cpp file:

// cpp

#include "ClassName.h"

void ClassName::MethodName() // definition (implementation)

{

// some code here

}

Initializer list

Not to be confused with “Member Initializer List” which is completely different!

In C++ you sometimes want a constructor with an arbitrary amount of inputs. Lets say we are making our own collection type, kinda like std::vector<> but fully custom made.

We will call it IntArray and it will hold an arbitrary amount of ints, what we want is to be able to construct it with any number of ints like you can with a normal array or vector,

what we want is something like IntArray array{ 1, 2, 3, ... };, we can make a constructor with std::initializer_list<int> for it to take any amount of arguments.

This is how we would do it:

// cpp

#include <initializer_list> // for std::initializer_list

#include <algorithm> // for std::copy

class IntArray

{

private:

int* array;

public:

IntArray(std::initializer_list<int> list)

{

// make the array the same size as the amount of args

array = new int[list.size()];

// copy all the elements

std::copy(list.begin(), list.end(), array);

}

}

Now we can initialize our custom collection type like an array or vector:

//cpp

// direct

IntArray array{1, 2, 3};

// copy

IntArray array = {1, 2, 3};

// explicit

std::initializer_list<int> list = {1, 2, 3};

IntArray array{list};

We can even use std::initializer_list<> in a regular function:

//cpp

Foo(std::initializer_list<int> list)

{

for (int i : list) // do something

}

And this is how you can then use this function:

//cpp

Foo({1, 2, 3}); // Correct

Foo(1, 2, 3); // Error

Member Initializer List

Do not confuse this with the similarly named “Initializer List” that is used to initialize aggregates with a list of values. These 2 concepts are very different.

In C++ when creating an object, member variables are initialized before the constructor body runs. If you assign to members inside the constructor body, you are assigning to already constructed members, this means unnecessary default construction followed by assignment. Member initializer lists allow members to be constructed directly with their intended values and are the recommended and sometimes required way to initialize members in C++, for example it it required when initializing const member or references.

In C# you would do something like this:

// csharp

class Person

{

private int a;

private int b;

public Person(int x, int y)

{

a = x;

b = y;

}

}

You can do the same thing in C++ but it is not the recommended way:

// cpp

class Person

{

private:

int a;

int b;

public:

Person(int x, int y)

{

a = x;

b = y;

}

}

In C++ this (member initialization list) is the recommended way:

// cpp

class Person

{

private:

int a;

int b;

public:

Person(int x, int y) : a{x}, b{y} // <- happens here

{

// this constructor body runs after

}

}

L-values And R-values

For the more advanced C or C++ topics we need to know what the difference is between an lvalue and rvalue. In simple terms,

and l-value is what is to the left of the = operator, and an r-value is what is to the right of the = operator.

But this is not a hard rule, there are exceptions.

L-value:

- is persistent

- has a persistent address in memory

- often has a name and an identity

- is often to the left of the

=operator - you can bind a reference to it with the

&symbol

R-value:

- is temporary

- has no persistent address in memory

- doesnt have a name and an identity

- is often to the right of the

=operator - you can bind a reference to it with the

&&symbol

Examples of L-values:

- variables

- functions

Examples of R-values:

- number literals (like

4) - expressions (like

x + 4)

Literals:

you might assume that all literals are rvalues because they are used temporarily most of the time,

and because they almost always are to the right of the = operator but actually is depends on the literall:

| Literal | Example | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number literal | 42 | Rvalue | temporary rvalue with no static adress |

| Character literal | 'a' | Rvalue | temporary rvalue with no static adress |

| String literal | "hello" | Lvalue | often used temporarily but has static adress |

| Compound literal | (int){42} | Lvalue | behaves like temporary but has static adress |

Code Example:

// cpp

// lvalue

int x = 10; // x is an lvalue

int* p = &x; // we can take its address

int& ref = x; // reference to an lvalue

// rvalue

int y = 4; // 4 is an rvalue, but y is not

int z = 5 + 3; // (5 + 3) is an rvalue

int w = x + 1; // (x + 1) is an rvalue

int&& ref = 4; // reference to an rvalue

// takes l-values only

void takes_lvalue(T& lvalue);

takes_lvalue(4); // fails

takes_lvalue(x); // works

// takes r-values only

void takes_rvalue(T&& rvalue);

takes_rvalue(x); // fails

takes_rvalue(4); // works

// takes l-values or r-values

// cpp has a weird rule where (const T&) can take either value

void takes_anyvalue(const T& value);

// takes l-values or r-values

// in templates T&& is a forwarding reference (universal reference)

template<typename T>

void takes_anyvalue(T&& value);

Move Semantics

Since in C++ the default is that all types are value types, this means that everytime you do x = y it copies over its data, now usually that is just a few bytes,

but if it is the case that a type holds huge amounts of data, then copying over that data every time you do x = y is a huge waste.

Because of this we have move semantics, it makes it possible for us to make it so this huge amount of data is not copied to some other place in memory,

but instead just stays where it is and only the ownership of the data is transferred (stolen) to the other variable you wanted to assign the data to.

Why Rvalues are needed in move semantics:

To distinguish between copy and move, we need to know if an object is temporary (rvalue) or persistent (lvalue).

T&“I can only copy this, because it’s a real object someone else owns.”T&&“I can steal resources safely, because this is temporary and no one else will use it.”

Example of implementing C++ move semantics:

// cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <cstring>

class CustomString

{

private:

char* ptr;

public:

// default constructor

CustomString(char* input = "")

{

ptr = new char[strlen(input) + 1];

strcpy(ptr, input);

}

// destructor

~CustomString()

{

delete[] ptr;

}

// copy constructor (copy over all data but leave original intact)

CustomString(const CustomString& other) // const because we want the other still intact

{

// duplicate all data in memory

ptr = new char[strlen(other.ptr) + 1];

strcpy(ptr, other.ptr);

}

// move constructor (transfer ownership without copying any data)

CustomString(CustomString&& other)

{

// move the pointer not the data

ptr = other.ptr;

// make the other pointer null (take away the data ownership of the other)

other.ptr = nullptr;

}

// copy assignment

CustomString& operator=(const CustomString& other) // const because we want the other still intact

{

// prevent copying to itself

if (this == &other) return *this; // return itself without changes

// duplicate all data in memory

delete[] ptr;

ptr = new char[strlen(other.ptr) + 1];

strcpy(ptr, other.ptr);

// return itself with the new data

return *this;

}

// move assignment

CustomString& operator=(CustomString&& other)

{

// prevent copying to itself

if (this == &other) return *this; // return itself without changes

// move the pointer not the data

delete[] ptr;

ptr = other.ptr;

// make the other pointer null (take away the data ownership of the other)

other.ptr = nullptr;

// return itself with the new data

return *this;

}

};

int main()

{

CustomString a = CustomString{"Hello"};

// copy constructor

CustomString b = a;

// move constructor

CustomString c = std::move(a); // std::move is just static_cast<T&&>

CustomString d;

// copy assignment

d = b;

// move assignment

d = std::move(c); // std::move is just static_cast<T&&>

}

Plain C Exclusive Features

people often say that all C code is valid C++ code, but that is hardly true, there are many things C can do that C++ can not do.

Designated Initializers:

Are used to initialize specific fields of a struct without having to init the struct members in a specific order. This feature was added in C++20, but most codebases are still using a lower version, making this mostly a plain C only feature.

In C# we would initialize a struct with specific field values like so:

// csharp

Person person = new Person()

{

age = 30,

name = "Alice"

};

In plain C the same can be done using the .variable syntax:

// plain c

Person person =

{

.age = 30,

.name = "Alice" // <- note how it has a dot before

};

In C++ (before C++20) you have to use the exact order in which the variables are declared:

// cpp

Person person =

{

30, // <- the int has to be first

"Alice" // <- the string has to be second

};

Compound Literals:

Are a C only feature that makes a temporary variable using the (type){value} syntax:

// compound literal for a basic type

int x = (int){42};

// compound literal for a typedef struct

Vec3 v = (Vec3){1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f};

// compound literal for an array

int* arr = (int[]){1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

Variable Length Arrays

A variable length array is an array whose size is not known at compile time but gets determined at runtime.

// plain c

// in both plain c and cpp you can have an array like this

int arr[16]; // <- size is known at compile time

// but in plain c you can also have an array like this (not possible in cpp)

int n = 16; // <- runtime variable

int arr[n]; // < size is determined at runtime

// you can even use it for runtime sized multi dimensional arrays

int matrix[rows][cols];

The limitations of a variable length array:

- they can only be on the stack, not the heap

- they can only exist in local scope, not global

- they can not be returned from a function (like any array)

- they can not be members of any struct

- they can not be

staticorexternvariables - they can not have an initializer at declaration like

int arr[n] = {1,2,3}; - they can not be used with

typedefto create a wrapper type